No animal is more synonymous with the Galapagos Islands than the giant tortoise. When Fray Tomás de Berlanga first discovered and briefly described the islands in 1535, he referred to the tortoises as galápagos. In Spanish galápago refers primarily to tortoises or freshwater turtles. It was much later, in 1815, when Captain David Porter wrote of his service in the Galápagos during the War of 1812, that he recalled that the carapaces of some of the tortoises reminded him of a type of riding saddle also called a galápago in Spanish. Thus tortoises with this type of carapace came to be known as saddlebacks. Over time, these two meanings of galápago became conflated, and so the conventional explanation emerged that the tortoises were called galápagos because they reminded Fray Tomás and the early Spaniards of the saddle. By calling the islands the Galápagos, we are, in essence, calling them “The Islands of Giant Tortoises!”

The giant tortoise is the symbol of both the Charles Darwin Research Station and the Galapagos National Park Directorate. In the form of one particular individual, Lonesome George, the sole surviving member of the Pinta Island species, the giant tortoise is the symbol of extreme fragility of the Galápagos islands, and a reminder of the need for vigilance and conservation. Sadly, Lonesome George died in 2012 without leaving progeny, and so his species, Chelonoidis abingdonii became extinct.

It was also the giant tortoise that tipped Darwin off to the incredible diversity of the Galápagos fauna and flora. In his Journal of Researches he noted:

I have not as yet noticed by far the most remarkable feature in the natural history of this archipelago; it is, that the different islands to a considerable extent are inhabited by a different set of beings. My attention was first called to this fact by the Vice-Governor, Mr. Lawson, declaring that the tortoises differed from the different islands, and that he could with certainty tell from which island any one was brought. I did not for some time pay sufficient attention to this statement, and I had already mingled together the collections from two of the islands. I never dreamed that islands, about fifty or sixty miles apart, and most of them in sight of each other, formed of precisely the same rocks, placed under a quite similar climate, rising to a nearly equal height, would have been differently tenanted; but we shall soon see that this is the case. It is the fate of most voyagers, no sooner to discover what is most interesting in any locality, than they are hurried from it; but I ought, perhaps, to be thankful that I obtained sufficient materials to establish this most remarkable fact in the distribution of organic beings.

The history of giant tortoise taxonomy is complex, and remains so even to this day. There are 15 recognized populations of tortoise in the Galápagos, all previously considered to be members of the genus Geochelone. Geochelone was presumed to be a cosmopolitan genus that included a cluster of species of small to medium-sized tortoises in South America, Africa, Madagascar, and Asia. In the past, giant species of Geochelone were once found on all continents except Australia, but today the giant forms are restricted to the Galápagos and the island of Aldabra. However, DNA evidence revealed that Geochelone consisted of four independent genetic lineages, one of which included the Galápagos tortoises and three small South American species, the red-footed-, yellow-footed-, and chaco tortoise. Thus Geochelone was subdivided and the South American cluster was renamed Chelonoidis. The name Geochelone was reserved for African tortoises.

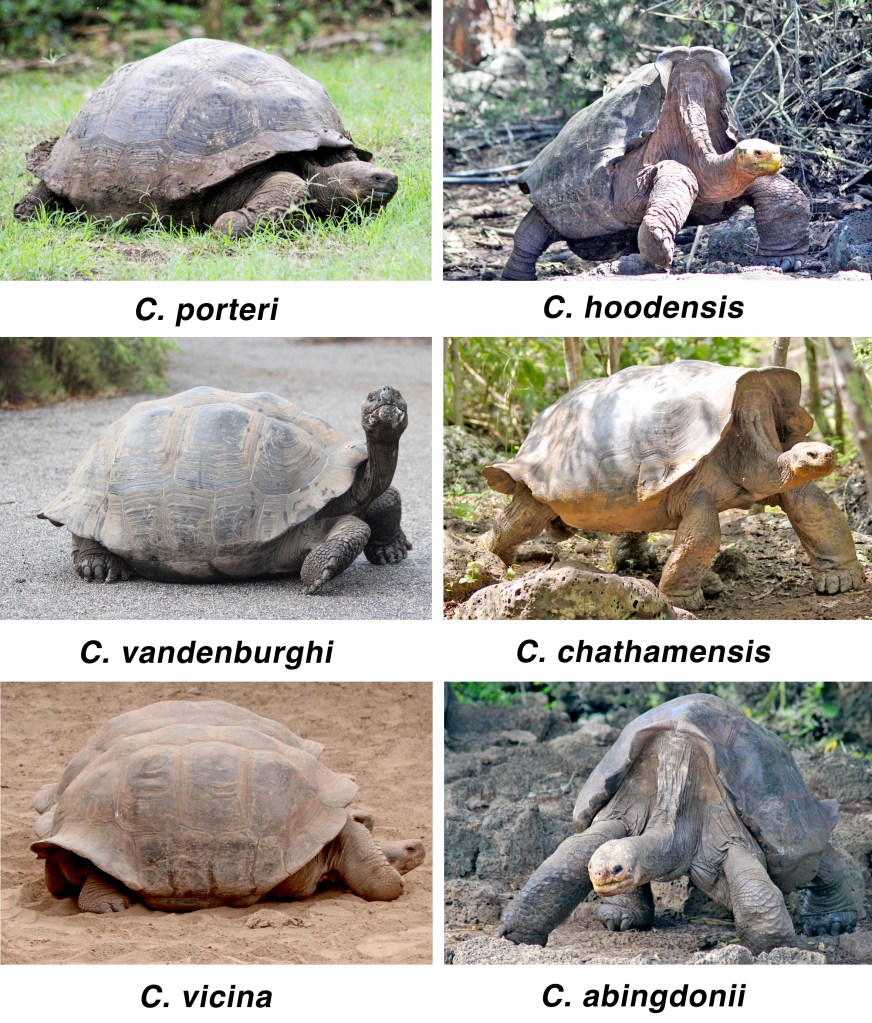

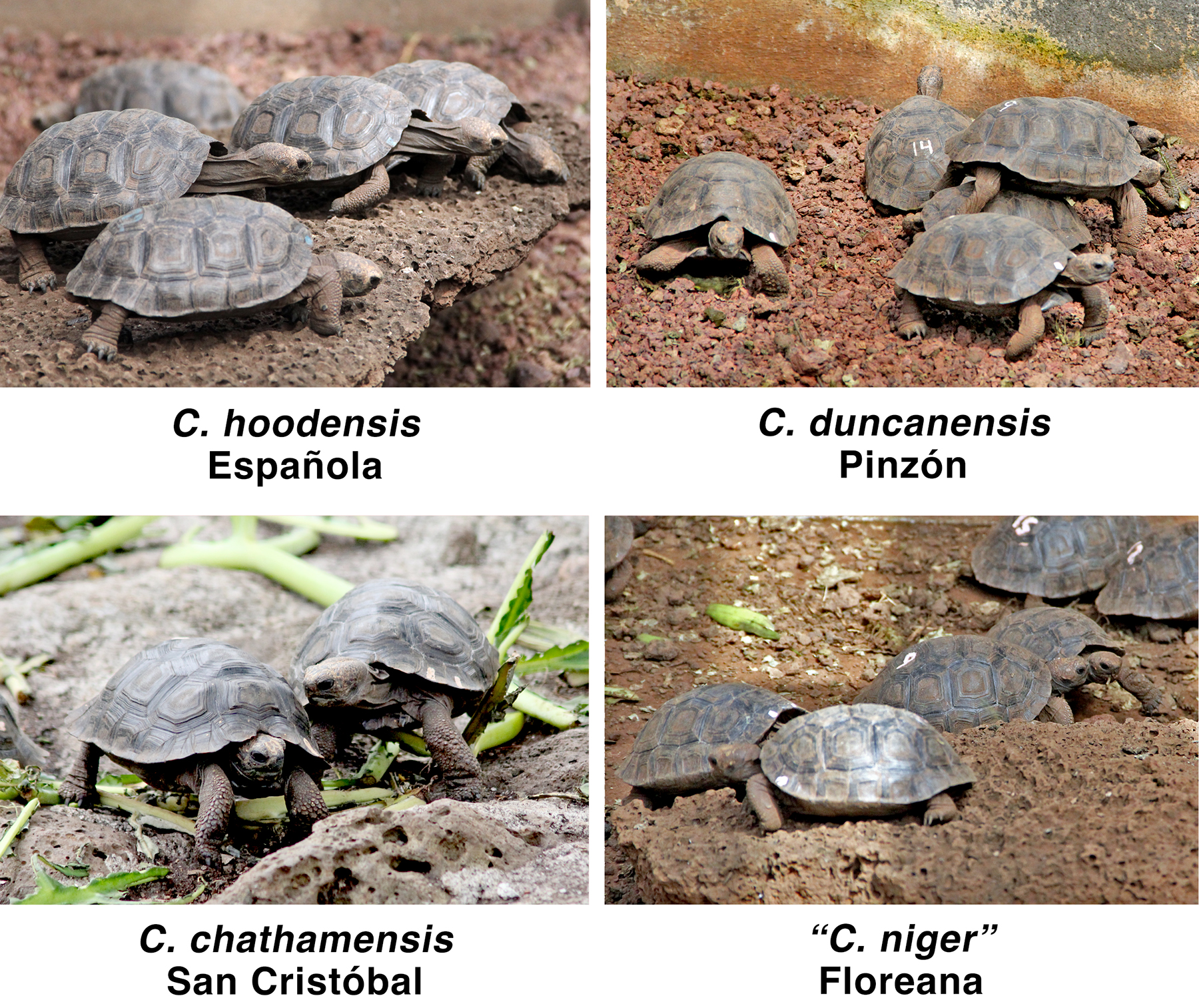

The taxonomic status of the 15 populations has been contentious as well: are they species of subspecies? All of the populations are identified on the table below. The earliest species name, niger, was applied to the Floreana population. Thus if all the populations represent a single species, it would be Chelonoidis niger. Consider the tortoise from Santiago. If the Santiago tortoise is a subspecies, it would be Chelonoidis niger darwini, but if it is a species, it would be Chelonoidis darwini. According to DNA analysis, the different populations represent independently evolving lineages, and so there is good reason to consider them as individual species, as I have done in the table below. To my mind, the species/subspecies debate is moot. What is important is the fact that the tortoises are on independent genetic trajectories, some farther along, perhaps, than others. The 15 species are:

| species | Island |

| C. hoodensis | Española |

| C. duncanensis | Pinzón |

| C. chathamensis | San Cristóbal |

| C. darwini | Santiago |

| C. becki | Volcán Wolf, Isabela |

| C. microphyes | Volcán Darwin, Isabela |

| C. vandenburghi | Volcán Alcedo, Isabela |

| C. guntheri | Sierra Negra, Isabela |

| C. vicina | Cerro Azul, Isabela |

| C. porteri | Western Santa Cruz |

| C. donfaustoi | Eastern Santa Cruz |

| C. phantasticus | Fernandina (survived by one female) |

| C. abingdonii | Pinta (extinct after death of Lonesome George) |

| C. niger | Floreana (extinct) |

| undescribed | Santa Fé (extinct) |

| C. wallacei | Rabida (doubtful species) |

Of the 15 species of Galápagos tortoises, three are extinct and one nearly so. Because of breeding and release efforts on the part of the Charles Darwin Research Station and the Galápagos National Park Directorate, most of the remaining species are holding their own. However, there is still on-going poaching of tortoises by local residents.

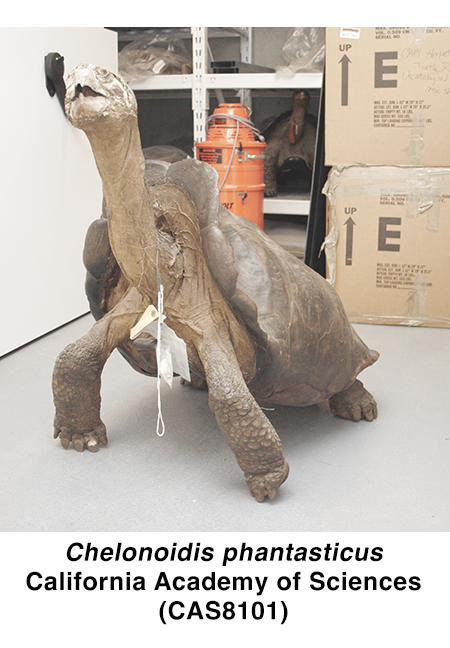

Originally, C. phantasticus, the Fernandina species was known from only one specimen, a male (CAS8101), found by members of the 1905/06 California Academy of Sciences expedition. Nothing more turned up until 1964 (!) with the discovery of putative tortoise droppings. However, no other tortoise, living or dead, had been found on Fernandina and it was entirely possible that that one lone male was a stray or a release. However, to everyone’s surprise, a live female was found on Fernandina in 2019. Genetic analysis of the female, named Fernanda, matched CAS8101. Thus C. phantasticus is indeed a real species. Subsequent searches have failed to turn up any additional live tortoises, and Fernanda may well share Lonesome George’s fate.

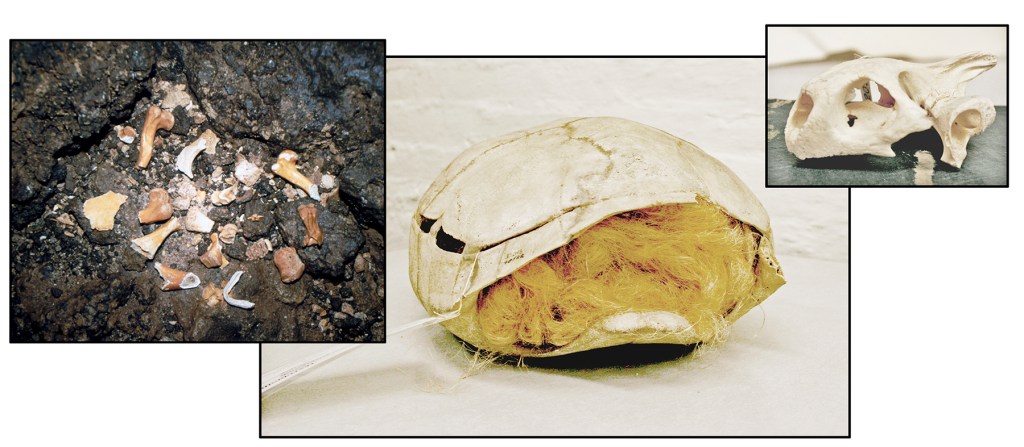

The tortoises on Santa Fé are also extinct. There are only 2 extant records of whalers removing tortoises, one from 1839 and the other from1853, the total haul being 22 tortoises in the first record, and only one in the second. There are also two eye-witness accounts of locals removing tortoises in 1876 and 1890. The 1905/06 California Academy of Sciences expedition found pelvic and limb bone fragments from 14 large individuals, two semi-fossil eggs, and a very old piece of dung, but no live tortoises. Later analysis of DNA extracted from these remains revealed that they represented a unique lineage. However, no carapace has been found and so it has not been possible to determine its morphotype. Consequently, the species remains unnamed.

The extinct species on Floreana, was still extant when Darwin visited in 1835. He noted that tortoises comprised the main food item in the colony; “two days hunting will find food for the other five in the week.” Although he commented on how the numbers had been obviously reduced from those in years past (“not many years since the Ship’s company of a Frigate brought down to the Beach in one day more then 200”), he did mention Vice Governor Lawson’s prediction that “there is yet sufficient for 20 years.” Indeed there is a well-documented record of heavy collecting in the years leading up to Darwin’s visit, but then just three years later, a visiting ship could find no tortoises and in 1846, another visitor declared them extinct. Descriptions of the Floreana species, C. niger are based on skeletal material from individuals who fell down into lava tubes and died. On my first visit to Galapagos in 1989 I saw such bones in the cave near the Post Office Barrel.

The Rabida species, C. wallacei, is known from only one specimen. Tracks were seen on Rabida in 1897 and a single individual was removed by the Academy of Sciences in 1906. No logs from whaling or sealing vessels which are known to have collected tortoises for food make any mention of collecting at Rabida. On the other hand, Rabida has a good anchorage and nearby are the remains of a corral in which tortoises, perhaps from other islands were temporarily held. The type specimen of C. wallacei, the individual from which the species was named, actually has an unknown provenance: it was assigned to Rabida because it resembled the one removed in 1906. Thus at this time, C. wallacei is not considered to be a valid species.

The 15 species of tortoises can be divided into two general morphotypes: domed and saddle-backed. In the domed tortoises, the front edge of the shell forms a low line over the neck while in saddle-backed tortoises, the front edge arches high over the neck.

Two of the above tortoises are international (really) superstars! C. hoodensis is represented by Diego, who is also highlighted at the head of this page. The Española population had been reduced to 14 individuals, 12 females and 2 males. They were all brought to the Charles Darwin Research Station to begin a captive breeding program. In 1977 a third Española male, Diego (originally designated “Tortoise 21”) was returned to the Galápagos from the San Diego Zoo to participate in the program where he became the prime stud, fathering hundreds of galápaguitos, baby tortoises. Ultimately, the breeding program was determined to be successful was terminated. On June 15, 2020, Diego and his companions were returned to Española to live out their days on their island home. And C. abingdonii, of course, is the late, lamented Lonesome George.

These differences are related to the environments in which the respective tortoises live, and the types of food they eat. The domed tortoises tend to live in the moist highlands and take their food from grasses and low-lying shrubs. The saddlebacked tortoises, on the other hand, live in arid regions and feed on plants that are mostly above their head, most notably the tree-like Opuntia (prickly pear) cactuses. The arched shell permits them to stretch their heads high, giving them a longer vertical reach.

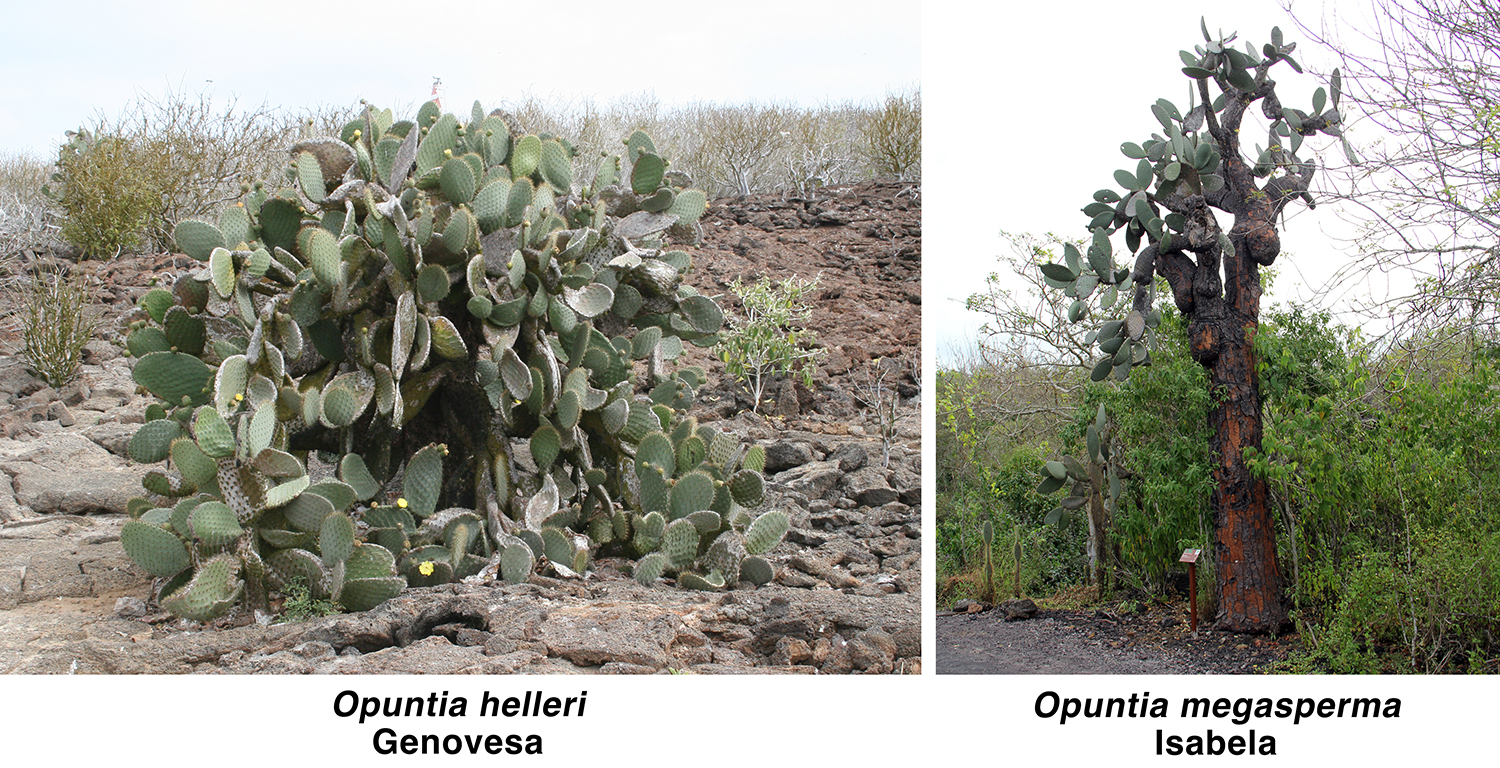

There is a very interesting relationship between tortoises and the various prickly pear cactus (Opuntia) species that inhabit the various islands. On those islands where there have never been any evidence of resident tortoise populations, like Genovesa, the resident species O. helleri tends to spread low over the ground and has soft, flexible spines, whereas on islands that have established tortoise populations, the resident species, like O. megasperma on Isabela tends to grow as trees. As young plants, the trunks are thickly covered with long, sharp spines which give way in older plants to a tough, tree-like bark. Thus, these Opuntias are inaccessable to the tortoise until the fruits, laden with seeds, fall to the ground, whereupon the tortoises eat them. The seeds pass unharmed through the tortoise’s gut and are dropped as the tortoise wanders from place to place.

There are several other interesting differences between the two morphotypes. Domed tortoises tend to be larger than saddle-backed tortoises. Two hypotheses have been presented to explain the size differences:

- small tortoises have require less water and energy, and can make better use of limited shade in dry environments, and

- large tortoises are more resistant to cooling during prolonged cloud cover typical of the highlands

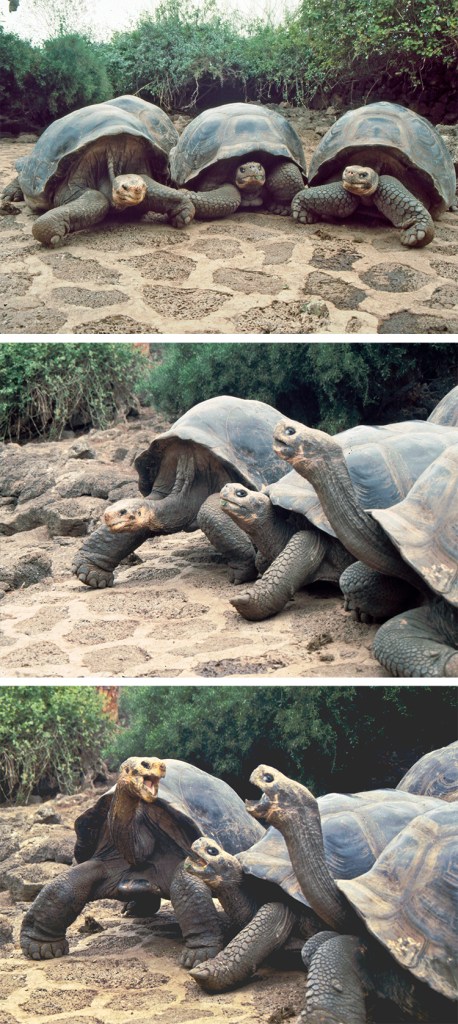

A second difference is that saddle-backed tortoises tend to be more aggressive and solitary while domed tortoises tend to be more gregarious. Aggressive displays are contests to see which of two combatants can raise their head the highest. The loser abruptly pulls its head back with a loud hiss and drops to the ground.

On one visit to the Galápagos, I was sitting in the tortoise compound on a cool, cloudy morning. As expected, there was little activity, but as the sun came out and everything warmed up, I noticed three tortoises, side-by-side waking up. As they became aware of each other, they began to raise their heads, mouths gaping, each trying to overtop the others. The arch in a saddlebacked tortoise’s carapace allows it to raise its head higher than a domed tortoise’s, and even though physically smaller, saddlebacks usually win these contests.

This aggressiveness might force the tortoises to become more solitary, thereby avoiding competition for food. Thus natural selection might favor the arched shell in dryer areas because it provides for greater reach while foraging as well as greater reach during combat.

Tortoises mate during the the rainy season, beginning in January. On the large islands, they gather in the wet highlands and begin copulating. The male mounts the female from behind (his plastron, the lower side of the shell, is concave to permit him to balance on top of his mate) and then, during copulation emits a loud groaning sound which can carry quite far. The significance of the sound is unclear. After copulation, the females make their way down to the lower, coastal regions where there are good nesting grounds. Using their bodies, they scoop out a shallow depression, 30-40 cm deep. The soil is softened with urine during digging. Finally, 2-16 round, hard-shelled eggs are laid and the nest is sealed with a cap of mud moistened with urine. A female can lay 4-5 clutches per season, usually between June and December. The eggs hatch 4-5 months later.

Right: C. guntheri, Arnaldo Tupiza Chamaidan breeding center, Isabela

In the pristine state, tortoises had few natural enemies – mostly Galápagos hawks, and possibly owls, that preyed on the hatchlings. But in the age of man, tortoise populations have been depleted by human activity both directly and indirectly. During the whaling era, the tortoises were highly prized by sailors for provisions because they could live for long periods of time without food or water, with little deterioration. In the days before preserved food, this was of great value to sailors who visited the Galápagos and carried off many thousands of tortoises. Because the interiors of the islands were so inaccessible, the sailors concentrated on the coasts and took away, therefore, massive numbers of breeding females.

Feral animals have also wrought havoc on tortoise populations. Pigs, dogs, and rats dig up nests and eat eggs and young. On Pinzón, for example, the only tortoises there were large and old. Despite signs of active mating and nesting, predation on hatchlings was so great that there likely had not been any recruitment into the population for 100 years. Goats directly compete for food and donkeys trample nesting areas and change the topography from forested areas to grassy plains.

Well into this century, people have continued to exploit the tortoises for food and oil. The photo below, showing the remains of hundreds of tortoises slaughtered on Isabela for oil, was taken in 1901 by Rollo Beck, who later was the leader of the 1905/06 California Academy of Sciences expedition, and this activity went on up until the foundation of the National Park in 1959.

Rollo Howard and Ida Menzies Beck Papers (Mss-036)

Since1959 scientists at the Charles Darwin Research Station and the National Park Directorate have begun a very successful two-pronged tortoise reclamation program. Eggs collected from tortoise nests in the wild and from breeding colonies at the station are hatched in incubators and the hatchlings cared for until they are big enough to be repatriated with a good chance of survival. The other part of the program is to eradicate introduced animals on the various islands. As a result, the Española population, for example, reduced to just 15 individuals, is now flourishing. Española progeny have been released to their home island, and are also being used to rewild Santa Fe and Pinta.

But despite the advances, tortoises are still in a precarious situation. In 1995 fishermen who were unhappy with new government regulations on sea cucumber fishing killed tortoises on Isabela and forcibly occupied the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz. If their demands were not met, they threatened, they would kill Lonesome George, noted above as the sole surviving member of the Pinta island race G. e. abindonii, and the symbol of the conservation efforts in the Galapagos. Volcán Alcedo, Isabela, long considered to have the healthiest population of tortoises, was over-run by feral goats. National Park Directorate closed Alcedo to visitors and began the successful “Project Isabela” to eradicate the goats. Wildlife trafficking is emerging as a new threat. In 2017, 29 galápaguitos were stolen from the Arnaldo Tupiza Chamaidan breeding center on Isabela, and another 123 went missing the following year. In 2021, 185 baby tortoises were discovered in a suitcase at the Baltra airport.

On my third trip to Galápagos in 1991 we hiked to the top of Alcedo. As we left the rim for the trek down, I looked back and saw my last tortoise for the day, slowly being enveloped by the gathering mists of low-hanging clouds. Despite intense conservation efforts, the Galápagos tortoise remains endangered.

Find out more about giant tortoises in Volume 1 of A Paradise for Reptiles.