Storm petrels, or “Mother Carey’s Chickens”, as they have long been called by sailors, are the smallest of the Procellariiformes. The name “Petrel” is thought to be derived from St. Peter, because their habit of not quite landing in the water, but dipping their feet in and fluttering over the surface while they feed on plankton, makes them seem as though they are walking on water. Storm petrels are difficult to photograph, as is evident from the pictures below. Usually seen from a distance, they are small and move about quickly, dancing on the surface of the water like so many butterflies. The photos below are enlargements of individuals from groups of petrels. Of the dozens of photos I have taken over the years, these are the best of the lot.

World-wide, there are eight genera of storm petrels, containing about 20 species. These eight genera are divided into two main groups, one inhabiting the northern hemisphere, and the other the southern, with some overlap in the tropics.

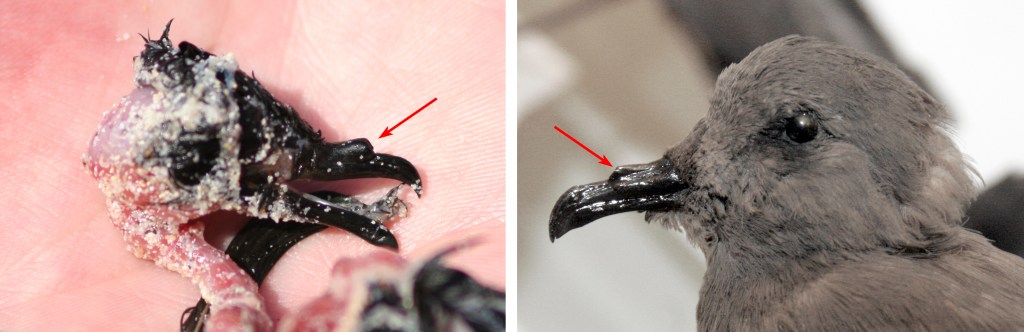

Typical of all procellariiformes, the nostrils of storm petrels lie in a tube at the rear of the beak. While only barely visible in the pictures of the live birds, the tube is obvious in the specimens below. The petrel on the left is the bedraggled carcass of a storm petrel on Genovesa that was being scavenged by a lava gull (Larus fuliginosis). The bird on the right is a mounted specimen of Leach’s Storm Petrel (Hydrobates leucorhous) at the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

In the Galapagos, there are three resident species:

White-Vented Storm Petrel (Oceanites gracilis galapagoensis)

Wedge-Rumped (Galápagos) Storm Petrel (Oceanodroma tethys tethys)

Band-Rumped (Madeiran Storm Petrel (Oceanodroma castro)

Of the three, Oceanites is a southern form while Oceanodroma is a northern form. Both the white-vented storm petrel and the wedge-rumped storm petrel are endemic Galápagos subspecies. Apart from the distinctive feather patterns, the white-vented storm petrel is easily identified by its long legs, which extend past the tail when the bird is in flight. The Band-rumped storm petrel is indigenous to the Galápagos, but rarely seen. Indeed, in more than 30 trips to the Galápagos, I have never seen one.Other species of storm petrels have occasionally been reported as vagrants.

Despite the fact that the white-vented storm petrel is a resident, endemic subspecies, its breeding sites have never been found. Autopsies of dead birds suggest that they lay their eggs from April to September. The other two species, both Oceanodroma, have well established breeding areas.

One well known site is on the cliffs above Prince Philip’s Steps on Genovesa. There, the birds nest in the numerous lava tubes and cracks that riddle the ground. The birds fly rapidly back and forth, seeming more like a swarm of gnats than a flock of birds. This area is also the only place where one can see short-eared owls (Asio flamemeus galapagoensis), an endemic subspecies, during the day. In the absence of Galápagos hawks, the resident owls are diurnal. The owls stand on the lava field and watch as petrels land and enter their dens. Then they wait by the opening to catch the victim as it emerges.

Typically owls eat all but the wings and breast bones. Even though owls on other islands are rarely seen during the day, their presence is evident via storm petrel remains. The remains in the photograph below were found on Plaza Sur.

The wedge-rumped storm petrel is the only one to visit its breeding site during the day, feeding by night. Thus, any day-time sighting of a feeding storm petrel will most likely not be the wedge-rumped. The wedge-rumped petrel breeds from April to October, laying one egg that is incubated by both parents. The band-rumped petrel likewise lays a single egg, but breeds in two groups, one from February to October, and the other from October to May. Like other storm petrels, and unlike its neighbor, the wedge-rumped, it feeds during the day, usually farther out to sea than the white-vented storm petrel, and returns to its nest at night.