If the giant tortoise is the symbol of the Galápagos Islands, then Darwin’s finches must be the symbol of evolution in the Galápagos. It may seem curious that of all the animals in the Galápagos,this group of very drab and dull birds is most closely associated with Darwin’s name. He was neither the first to see them (they are mentioned in passing by Captain James Colnett in 1798) nor did they figure much in his writings subsequent to his Journal of Researches. Despite the fact that they intrigued Darwin, they are far too complex a group of animals for him to have fully understood them. Moreover, he was halfway through his sojourn in the Galápagos when he realized that each island had its own set of species, and so his specimens were mixed. Nevertheless, the finches played an important role in helping Darwin recognize the reality of the evolutionary process. In the first edition of his Journal of Researches (1839), he wrote:

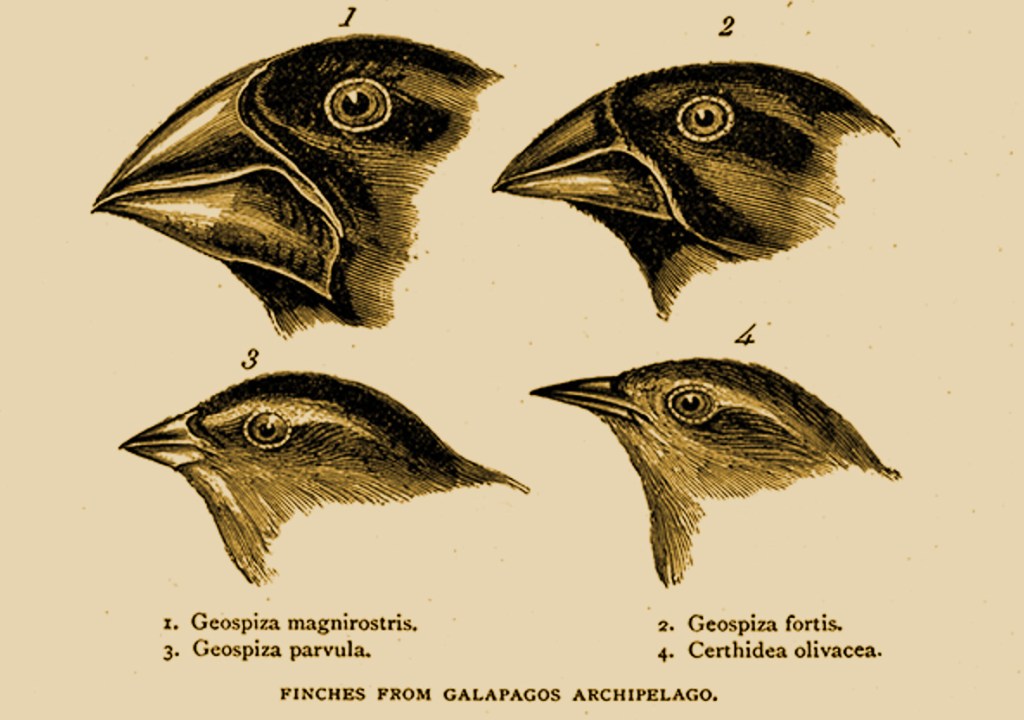

It is remarkable that a nearly perfect gradation of structure in this one group can be traced in the form of the beak, from one exceeding in dimension that of the largest grosbeak, to another differing but little from that of a warbler.

By the time he published the second edition (what we now know as The Voyage of the Beagle) in 1845, Darwin more or less had his theory of evolution by natural selection in place, but was keeping mum about it. Nevertheless, he hinted at it, most strongly in the Galápagos chapter. In the second edition he wrote of the finches :

Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.

And he included this famous illustration:

The name Darwin’s Finches was first applied in 1936, and popularized in 1947 by the ornithologist David Lack, who published the first modern ecological and evolutionary study of the finches. Today Darwin’s finches are the subject of intense study, and they are revealing much about the evolutionary process.

During an early trip to the Galápagos, one of my students wondered why we need to worry about naming them; why can’t we just enjoy them for what they are? There is power in a name; to know the name is to understand the named. This is especially so in that branch of biology known as taxonomy or systematics. The taxonomist not only applies a name to an organism, but, by ranking those organisms into hierarchies of names, attempts to portray evolutionary relationships. Within the hierarchy, the only “real” entity is the species. The higher groupings are merely assessments of how species are thought to be related to other species, and different taxonomists may very well disagree.

Traditionally, 14 species of birds have been recognized as Darwin’s finches – 13 in the Galápagos, and one on Cocos Island. Subsequently, several Galápagos species have been split, yielding 17 species. The Galápagos finches are currently divided into four groups, each representing a single genus:

- Geospiza: ground and cactus finches

- Camarhynchus: tree, woodpecker, and mangrove finches

- Certhidea: warbler finches

- Platyspiza: vegetarian finch

Although it is not present in the Galápagos, Pinaroloxias, the Cocos finch is closely related to the Galápagos species, and is also considered to be a Darwin’s finch.

With the understanding that the higher hierarchies are assessments of relationships, individual taxonomists may differ in their assessment. At one time, the birds assigned to Camarhynchus were seen to be too heterogeneous to belong to the same genus, and so the woodpecker and mangrove finches were separated into the genus Cactospiza. On the other hand, finch expert David Steadman had argued that splitting the finches into multiple genera emphasizes their differences and suggested that all of the finches be united in the singe genus Geospiza to emphasize their similarities!! The table below gives the genus and species names for all of the finches and photographs of all the finches that are accessible to visitors:

Of the three finches for which I do not have photos:

- The sharp-beaked ground finch, Geospiza dificilis is rare and found only in the highlands of Santiago and Fernandina, which are not open to visitors.

- The vampire finch, Geospiza septentrionalis is confined to Wolf and Darwin, which are only open for scuba tours.

- The mangrove finch is found in only a few small locations in western Isabela that are not open to visitors. It is highly endangered.

Among the original 13 species:

- Initially, a sharp-beaked ground finch, Geospiza dificilis, was found on Genovesa and the highlands of Santiago and Fernandina. Subsequently the Genovesa population was split off and assigned the name Genovesa ground finch, Geospiza acutirostris.

- The Genovesa cactus finch, Geospiza propinqua was originally considered to be a subspecies of Geospiza conirostris (the large cactus finch, Geospiza conirostris propinqua) but was subsequently raised to full species status.

- The warbler finch, Certhidia olivacea, was split in two, the green warbler finch, Certhidia oivacea and the gray warbler finch, Certhidia fusca.

It takes some effort and interest to learn to identify the finches. Their salient difference is the size and shape of their beaks. What makes Darwin’s finches so difficult to identify is that the beaks of a single species can be variable (which can sometimes be exacerbated by interbreeding) and the fact that the beak of one species may overlap into the range of another. Moreover, Darwin’s finches share similar size, coloration, and habits. Michael Harris, the author of a popular Galápagos bird guide book cautioned: “It is only a very wise man or a fool who thinks that he is able to identify all the finches which he sees.” Early in my travels I was quite intimidated by the finches. Indeed, for several years I simply filed away my photographs without really looking at them until finally I could work up the courage to try. With finches, it is often a question of shoot now and ask questions later. Sometimes I realized that I saw some particular finch only after the trip when poring over the photographs. I had many discussions with guides (my friend naturalist guide Peter Freire’s ability to identify finches is uncanny), and one year, I even brought my slides with me. At this point I feel somewhat confident in my identifications, but I am always mindful that “it is only a very wise man or a fool who thinks that he is able to identify all the finches which he sees.” The best way to begin is to look at finches on islands that have relatively few, distinct species (see the table below).

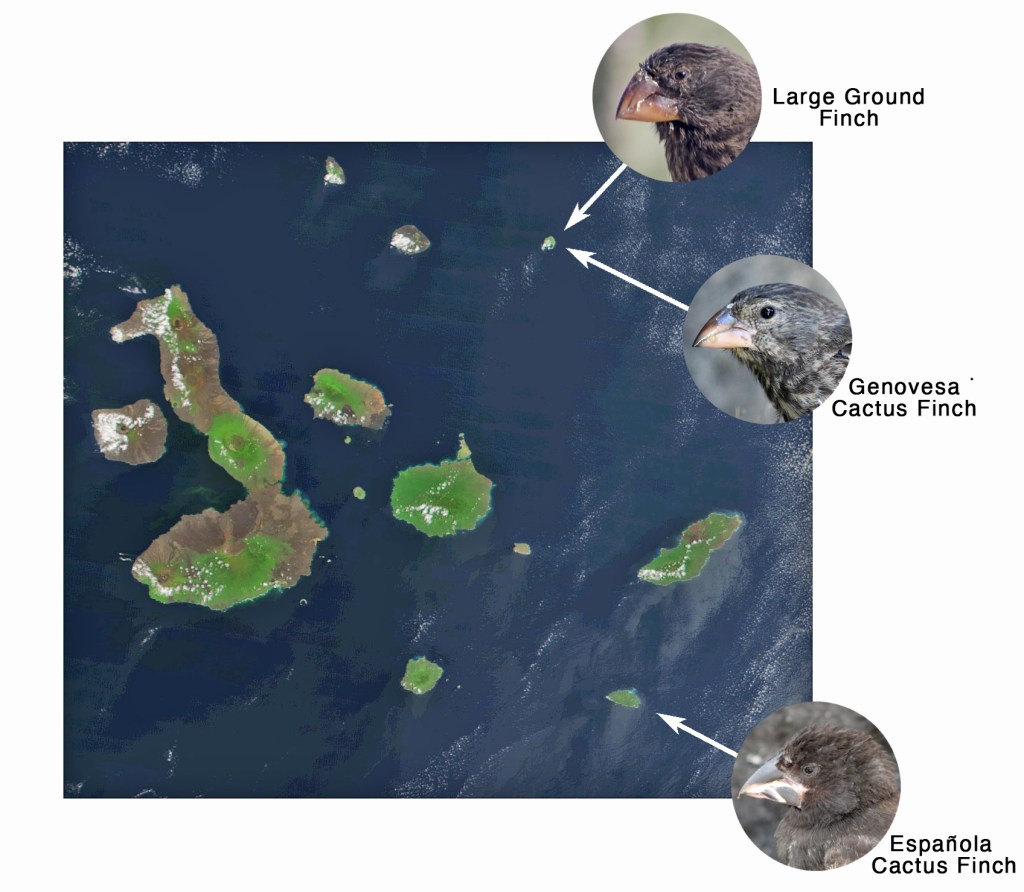

These four birds are good examples of the difficulty in identifying finches:

Finch #1 looks like a large ground finch and probably is, but according to the bird guide, a finch that looks like a large ground finch but is in a mixed flock is probably a medium ground finch that is at the very large end of the medium finch range. Large ground finches are more solitary than medium ground finches. I photographed finch #1 at the tortoise pool at the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz and there were lots of medium ground finches around that day. Finch #2 is definitely a large ground finch because I photographed it on Genovesa.. I always thought that Finch #3 was a small ground finch. I photographed it while anchored off Daphne Major. The bands indicate that it is part of the study by Peter and Rosemary Grant. The finches on Daphne Major are predominantly medium ground finches, but they tend to be small. Finch #4 is definitely a small ground finch because I photographed it on Espanola. The table below shows the distribution on islands that have visitor sites

The difficulty in identifying the finches is rooted in precisely what makes them so interesting and important – the evolutionary process. If we accept that two species share a common ancestor, then as one traces the species back in time, they should become closer and closer in form. At the branch point, the species should become ambiguous. That is precisely the point at which we find the Darwin’s finches. They are in the process of separating, but they haven’t completely done so at this point in time.

One definition of a species includes the presence of a fertility barrier between individuals of different species. In the case of Darwin’s finches, those barriers are not completely formed yet, and there is a certain amount of documented hybridization between species. This also contributes to the ambiguity of the birds.

Comprehensive studies, both morphological and genetic, by Peter and Rosemary Grant and their colleagues over the past few decades (reviewed in a more accessible layman form in The Beak of the Finch) have revealed many interesting lessons about the evolutionary process. Our current understanding of evolution is that new species are born when a local population of the ancestor species becomes separated from the main population (i.e. it becomes allopatric). Once the gene pool is separated, the two populations may be subject to different natural selection pressures, and hence, evolve in separate directions. The splitting of a population followed by subsequent evolution is known as allopatric speciation. At some point, the populations may come back together again, that is, they may become sympatric.

Finch evolution seems to be driven by a combination of allopatric and sympatric events. As finches move from island to island, they become adapted to the various environments that each island may offer. Such island hopping will eventually cause previously isolated populations to meet up. A variety of possibilities arise when two populations, born in allopatry become sympatric:

- If the two populations have not diverged too greatly, then they can simply merge back into a single population

- The two populations may compete, one eventually becoming extinct

- The two populations may avoid competition by specializing. In this case, they would continue to diverge in sympatry

The cactus finches are an interesting example. There are three species but none of them coexist on the same island. The Española and Genovesa cactus finches shows what can happen in the presence and absence of a competitor species.

On Genovesa, the cactus finch coexists with the large ground finch. During the wet season, when there is lots of food to go around, the two species can feed in each others niches with no competition. However, the dry season, and its scarcity of food forces the two to specialize. Assuming that the two originally evolved in allopatry, their association in sympatry has continued to make them diverge. Despite the fact that finches show a broad variation within each beak type, the diversity of beak shape and size in the large ground finch and the Genovesa cactus finches is minimal. Any large cactus finch whose beak varies towards the large ground finch will be unable to compete with members of its own, or opposite species. The same applies to the large ground finch.

The picture is quite different, however, on Española. There, the large ground finch either never arrived, or it became extinct. Whichever is true, Española has only the large cactus finch. But with no competition, the beak of the large cactus finch can exhibit more of its variability and, in fact, its beak is somewhat intermediate between the two finches on Genovesa, and it can feed equally well in both niches all year round. This phenomenon is known as character displacement.

Darwin’s finches have many other evolutionary tales to tell.

Even though the finches never made their way into On the Origin of Species, Darwin used them in his Journal of Researches to quietly announce the theory of evolution by natural selection. As such, it is entirely appropriate that these small birds carry the name of the scientist who gave the theory of evolution to the world, and who put their island home on the intellectual map.